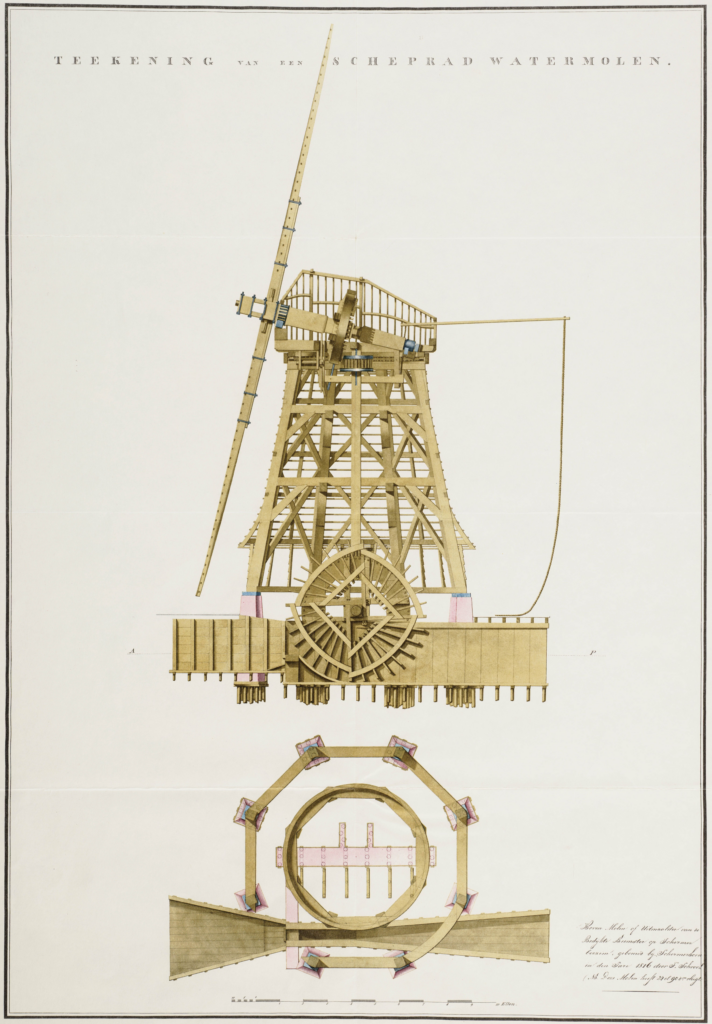

The Netherlands is inseparable from its windmills. You see them in every corner of the country, from the postcard-perfect waterways of Kinderdijk to the scattered polders of North Holland. They are a symbol of Dutch ingenuity, a testament to a people who tamed water and carved habitable land from lakes and marshes. Some mills pumped water, some ground grain, and some even powered small industries, long before electricity was a thing. There were sawmills (cutting logs), oil mills, paint mills and mustard mills, as well as paper and pepper mills. All worked hard for centuries, helping shape daily life and industry in this country.

I’ve always been fascinated by the view of a windmill standing in the middle of open fields. Before moving to the Netherlands, I often used photos of this landscape as my desktop background. Whenever work felt stressful, I would look at those windmills — covered in snow, or surrounded by morning mist — and I would relax a bit. After moving to the Netherlands, I had the chance to see many of them in real life, some up close, and I even climbed a mill or two! But the ones I visited from the inside were always industrial mills, like those at Zaanse Schans. When I later moved to Alkmaar, I started doing regular walks through the Oudorperhout nature reserve, where a few windmills still stand. To my surprise, I found out they were inhabited. Once I learned that, I couldn’t stop wondering what life is like for the people who live there, and how one ends up calling a windmill home. So I had to discover that and tell you about it as well.

From the approximately 1200 windmills currently in the Netherlands, about 150 are inhabited. On the outskirts of Alkmaar, in the Oudorperhout nature reserve, there are five windmills. Four of them, known as B, C, D, and E, are drainage mills, or strijkmolens in Dutch, designed to pump water. The fifth is a flour mill, ’t Roode Hert, where visitors can buy flour and other bakery products. The fours strijkmolens were built between 1627 and 1630 and have been restored several times since. They were functional until WW2, but now only one can actually pump water, while the others are able to turn their sails, without performing their original function. You can see here the timeline of Molen D. All four drainage mills are now inhabited by people who are trained as millers and their families. Although the mills are private residences, they can be visited on special occasions such as Windmill Day (on 9 May in 2026) and Heritage Days (Open Monumentendag, on second Saturday in September).

The mill I’m introducing today is Strijkmolen D (Mill D), an octagonal, thatched inner mill, inhabited and carefully maintained by miller Tom Kreuning (who is also a medical doctor). To reach the windmill/house, you have to open an old-fashioned door and enter the well-manicured courtyard. Molen D is surrounded by a small courtyard, with a lawn, a garden, and chickens pecking their way through the scene. Tom is a passionate beekeeper, so you can also see beehives in the garden.

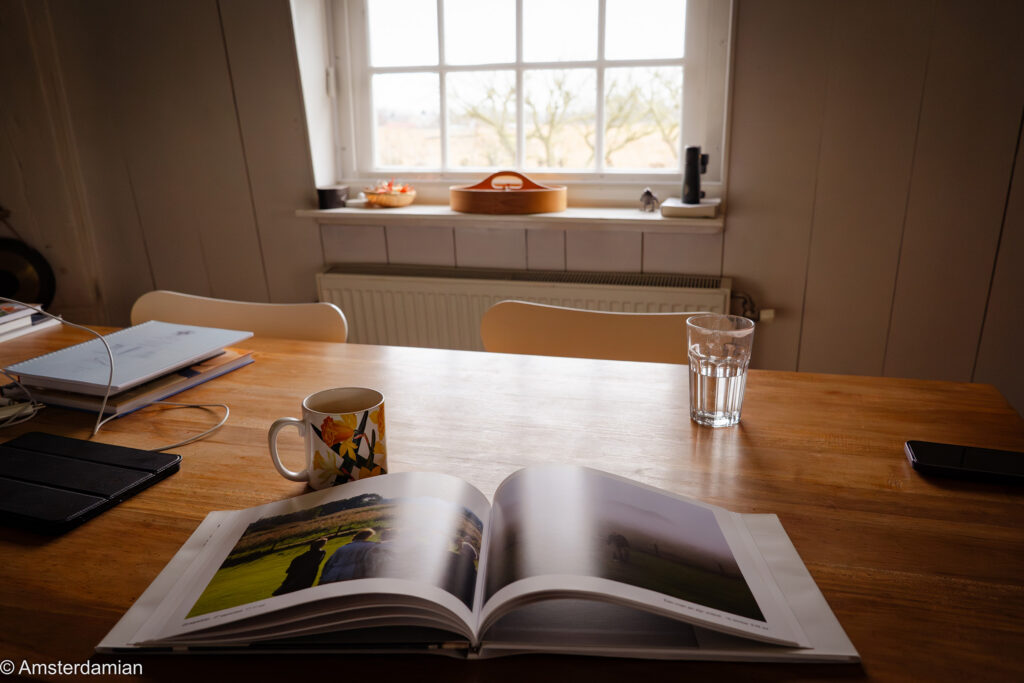

Tom received me in the cosy kitchen and started preparing a very Dutch lunch: cheese sandwiches. As soon as you enter the house, you feel its cosiness welcoming you. The space is not big, but it’s bigger than I imagined it would be. Talking to Tom, I could immediately see the passion for windmills in his eyes and hear it in his voice. It’s not every day you meet someone who got to make a life around their passion, who got to live it fully, and this kind of person inspires me so much. We took the sandwiches and tea and sat down at the table in the seating area, with a small window offering a view over the natural reserve. Tom told me how, in the past, this space downstairs would have been the entire living quarters of a family of sometimes 12–14 people, and how it would also contain part of the mill mechanism. Now, the house has three floors, with all the amenities, and it’s built kind of like a box inside the windmill body and around its beam structure. Here, Tom and his late wife Joan shared a life and raised their child, with the windmill witnessing it all. Such a special life!

“From my very early memories I was crazy about windmills, Tom says. “I was cycling all over the Netherlands to see them. This was before the internet, so it was very hard to get information.” As he spoke, I imagined a young boy cycling across the Netherlands in the 1970s and 80s, visiting every mill he could find to learn everything he could about them. “When you want to move to a windmill, you have to be a miller. We have a guild of millers, and they do the teachings and the trainings to become a miller.” Tom first joined the Dutch Mill Society, De Hollandsche Molen. At the time, he was training to be a medical doctor, so his miller aspirations had to wait. “I didn’t have time to do the windmill training then,” he said. But once he finished his medical studies, he joined the guild, taking weekends to learn the craft. “During the week I was a doctor, and on Saturdays I was trying to become a miller. That’s a big hobby,” he laughed. Balancing family life and study meant it took him four years before he became a certified miller.

The process of becoming a miller sounded intimidating. “There was one big exam. Three old guys from the guild examined you and it was really scary. In the old days, lots of people failed. Luckily, I passed the exam. I said, well, this was harder than my medical doctor’s exam!” I could almost picture the tension of that day, standing under the turning sails, trying not to let a misstep ruin years of preparation. Luckily nowadays things have changed to an easier system, with more than 90% of the candidates passing the exam.

Living in a windmill was never the goal at first. He started by caring for a small mill in Alkmaar, behind the Central Station. “I didn’t become a miller to live in a windmill. Just to have fun,” Tom said. But fate intervened when neighbouring mills became vacant. “The people who lived in one of these neighbouring mills moved out. My friend called me and said, ‘Maybe you should take a chance.’ First, my neighbouring mill was empty, and then this one became empty. I talked to the provincial government, which was the owner. They said I could have the key to Molen D and keep it up a little, but there was no guarantee I could live here in the future.”

It was only after a nearby mill burned down, the result of years of being left empty and children playing with fire on its premises, that the authorities acted more decisively. “Then the mills were taken over by the Molenstichting Alkmaar (Alkmaar Windmill Trust). They restored the mills, and then we made the living quarters with lots of help from friends and family,” he explained. Professional windmill builders handled the structural restoration, which took about one year, but Tom’s family and volunteers worked on the interior, insulation, heating, and plumbing. By 2002, the family had moved in. I could sense his pride as he described this transformation: an abandoned mill reborn into a warm, functional home.

“We used to live on the other side of the park. We could see this windmill from our bedroom window. And then my wife was okay moving here because she thought, well, if I had my hobby at home that would be an advantage. It meant I didn’t have to go away to a windmill an entire day or weekend. And also she liked this spot because it’s very close to facilities, the city centre and shops. Because if we would have lived in the Schermer polder, in the middle of nowhere, it would have been more difficult.“ Living in a windmill comes with responsibilities, both practical and symbolic. “I pay rent to the Windmill Trust. I do small maintenance, like garden work and painting. For bigger jobs, the Trust pays for a mill maker, painter, or thatcher. You can’t make major changes; these are national monuments.”

Replacing the rods of Molen D in 2023:

I looked around at the tall wooden beams, the narrow stairs, and the view from the upper windows. “It’s the best view,” he said, as if reading my thoughts. On the other side of the mill, the train station and schools were visible. The windmills themselves are protected, yet the threat of encroaching development is real. “I hope no tall buildings will be built in that area. If a high-rise is built too close, the windmill can’t catch the wind properly. There are rules to protect them, but economic interests often outweigh historical preservation.” As I explored the living space, it became clear that being a miller is more than a hobby; it is a craft, a way of life, and a living piece of history. “I’m now an official instructor. Students come to me; I teach them the craft of the miller which is now recognised as UNESCO intangible cultural heritage.”

He shared the history of the Millers Guild, founded in the late 1960s to preserve both the craft and the mills themselves. “A couple of guys tried to write down everything from the old millers. They saved lots of mills and trained more than 2,500 millers. About 1,500 are currently active today.” They collected and preserved knowledge from the old millers, and put it all together so they could pass it on to the next generations. It’s remarkable to think that without the intervention of a few passionate people, these windmills and the skills needed to operate them might have disappeared entirely.

The windmills were once vital to water management. Nowadays, they are replaced by more modern methods, although they are still used when it rains a lot. “These mills pumped water from one canal to another. This one (Molen D) did it until 1941. There are about 57 mills here in the province of Noord-Holland that can still pump water in times of surplus rains. The waterboard owns about 19 of them and they are being kept in good shape.” With climate change bringing more frequent surplus rains—and with much of the land lying below sea level—these mills are increasingly called upon to help keep Dutch feet dry. Tom recounted how a friend had to pump water day and night using the windmill, when an electric pump in the polder failed, a vivid reminder that these structures are not just historic curiosities, but functional tools crucial to Dutch life.

The ingenuity of Dutch windmills extends beyond water management. “People ask me if the windmill was invented in the Netherlands. No, it wasn’t. The technique came from Asia. But here in Holland, we used them for many processes: flour, oil extraction, sawing wood. The first industrial use of wind power was right here in Alkmaar. The first mill that pumped water in 1407 was here in Alkmaar. The first oil mill, using a special process to extract oil from seeds, was also here in Alkmaar. And also the saw mill to saw big trees into planks, that’s also an invention from this area.”

Even as a residence, the mill has a role in public education. “It’s a national monument. I don’t own it; I’m the custodian. And I have to spread the word, show people what it is, and pass it on to the next generation. That’s what I already did with my son, who is a miller as well. Twice a year, the windmill opens for visitors: Windmill Day in May and Open Monument Day in September. On those days, up to 300 people climb the stairs, curious about life inside these iconic buildings, and then I have lots of friends who help me because it’s too busy.”

I asked Tom if I could become a miller, and, apparently, it could be a thing, if I really wanted to. “There are certain requirements: you have to be mentally and physically fit. Then you follow instruction, similar to being an apprentice to a master. Experience is the most important part. The guild requires at least 150 hours, but instructors can decide when a student is ready. You can join any time of year—it’s not like school starting in September. It’s also the cheapest education in the Netherlands; you only pay for the guild membership. Still, before becoming a member, people should visit some windmills and join a day of training to see what it’s like and whether it’s really something for them.” All the handbooks are free to download from the Guild’s website, so if you are curious, go ahead and get them.

We then went on to visit the rest of the house and up to the mechanical mechanism of the windmill, on the top floor. I could see the thatch covering the windmill up-close, and found out it has no insulation role; it’s there just for water drainage. And then I could see and touch the big wheels, built around 1700, while Tom explained how they work. There was no wind that day, so we couldn’t set the sails in motion. As he showed me how the windmill functions, I realised I wouldn’t be physically fit for this job, as it takes quite a lot of strength to turn the sails, pull the brake, and handle all the other tasks required.

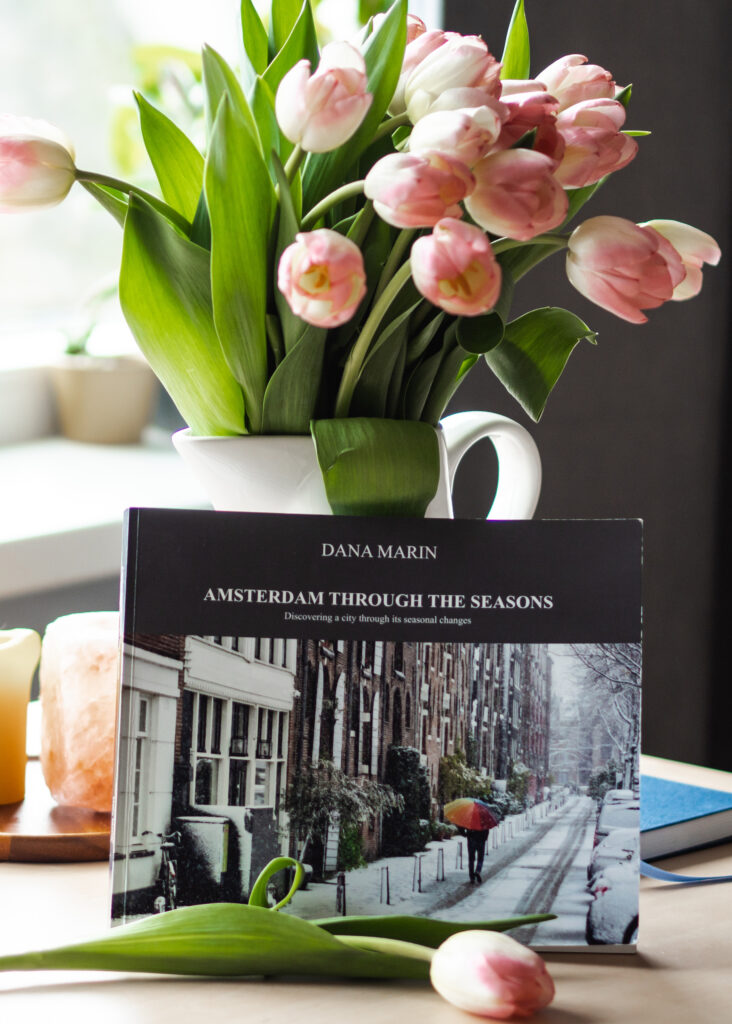

Before I left, Tom showed me the photo book his wife made — Het keukenuitzicht — with photos of the view from the kitchen window. It’s a beautiful book showing the changing of the seasons but also people and activities happening around the windmill at different moments.

Leaving the mill, I paused at the gate, looking back at it. There is something ineffably Dutch about this scene: the combination of practicality, history, and daily life, all intertwined with the land and the wind. The Netherlands and windmills, they truly belong together, and I felt lucky that for a few hours I had glimpsed a life that balances heritage and home, work and passion.

If you want to learn more about Tom and his mill, check out his website: Molen D, and the Instagram account. He does a great job documenting everything, from history to reparations, from plants and wildlife that live in the courtyard to information about the nature reserve, answering frequently asked questions and much, much more. It’s in Dutch but you can easily use Google Translate to understand everything.

There is also a YouTube channel where you can watch videos: @StrijkmolenD.

To learn about all the windmills in Alkmaar, check out the website of Molenstichting Alkmaar.

Stay tuned for more and follow Amsterdamian on Instagram and Facebook for more stories about life in the Netherlands. Please share this post if you liked it!

Check out my photo book: Amsterdam Through the Seasons!

Love what you’re reading? Support my work with a small donation.